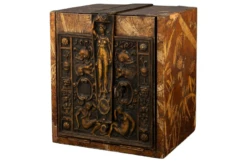

Antique Italian Jewelry Box Casket – Attributed To Jacopo And Lodovico Del Duca

$343.00 Original price was: $343.00.$99.99Current price is: $99.99.

- 7-Day Returns, 100% Quality

- Get the Best for Less

- Fast and Secure Payments

- Peace of Mind with Every Purchase

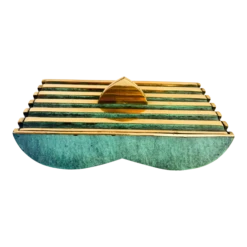

A scarce antique Italian fall-front jewelry box with lockplate and hasp attributed to Jacopo and Lodovico del Duca.

Lockplate and …

A scarce antique Italian fall-front jewelry box with lockplate and hasp attributed to Jacopo and Lodovico del Duca.

Lockplate and Hasp designed circa 1570, date of manufacture unknown, attributed to the late 16th century Roman foundry of Jacopo (c. 1520-1604) and Ludovico (fl. 1551-1601) del Duca.

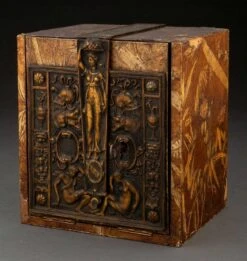

The rectangular drop-front box casket, circa 1880, signed L’PUPLET, features an earlier finely cast gilt bronze lock plate with a coat-of-arms and hasp, mounted on drop-front chest of drawers form box covered in embossed and gilded paper, having fall-front panel opening to reveal three interior drawers, all lined in red velvet.

The wallpaper covering the box’s exterior features bamboo, birds, and flowers in the Japanesque taste popular in Europe in the 1870s and 1880. To the interior of the fall front is a circular stamp with the name of the workshop or store (possibly L’PUPLET) somewhat obscured, and the city “Burxelles” indicating that the box was likely made or retailed in that city in the late 19th century.

Marks to box:

L’PUPLET, BRUXELLES

Inscription:

13, 14, 15 (Interior drawers inscribed on the verso of their backboards in script from top to bottom, respectively)

Provenance / Acquisition:

The origin of the elaborate lockplate with hasp on the front of the piece is more intriguing. At least 76 lockplates of this design have been recorded in major museums, private collections, and in the antiques trade across the Western World. For example, lockplates of this pattern are in the collections of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the State Museum of Prussian Cultural Heritage in Berlin, the Museum Cicico in Bologna, The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Dallas Museum of Art in Texas, the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, the Museo di Palazzo Venezia in Rome, the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.[1]

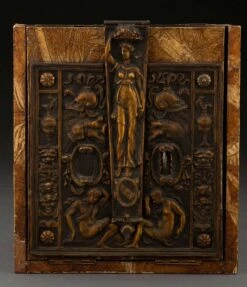

Specialists in Renaissance bronzes, especially Charles Avery and Lukas Madersbacher, have assembled robust inventories of such pieces and have attempted to decode the late Mannerist iconography, family coat-of-arms, and use of these amazing objects.[2] Madersbacker published a study in 2021 where he argues that the female figure on the hasp is that of Dovizia, a kind of ‘house goddess’ guaranteeing prosperity and fertility; and that this image was likely based on a prototype from the Italian Renaissance sculpture Donatello. The male-female pair of reclining, nude warriors who have cast off their armor above have not yet been identified, but according to Madersbacker fit well into an iconographic tradition of such pairings.[3]

Originally the use of such lockplates in the late 16th century was to ornament and secure travel chests in which wealthy individuals could transport their personal belongings as they moved between homes and other locations.[4] Many of the lockplates include the coats-of-arms of wealthy Italian families who owned them, and it is believed that a significant number of examples were made to celebrate marriages between powerful families. Others appear to have simply been made as luxury items to adorn and identify the owners travel chests. The coat-of-arms on the hasp is believed to be that of the Gras-Préville family of Italy and southern France.[5]

The exact dating and creator of this lockplate design has eluded scholars, but Madersbacker, building on the earlier work by Avery, argues that the earliest known example was made to commemorate a marriage that took place in Rome in 1569 and that such lockpates continued to be made in significant quantities until at least c. 1600.[6] He further postulates that this time period, along with the fact that most of the families who commissioned chests with this lockplate design lived in or were connected to Rome, suggest it is possible that they were produced in the shop of brothers Jacopo (c. 1520-1604) and Lodovico del Duca (active 1551-1601). Jacopo was well known at the time as a sculptor and architect who is most remembered for assisting Michelangelo with projects in Rome, including the sculpture and construction of the tomb of Pope Julius II.[7]

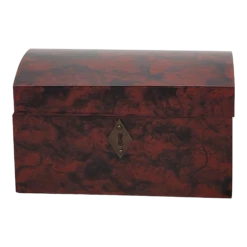

Several of these lockplates with hasps survive on their original domed-topped chests, but the vast majority do not. Rather, they were retained once the usefulness of the chests was over and subsequently introduced into the European antiques trade in the 19th century.[8] Furthermore, it is believed that later examples were made although the chronology for this work has not been delineated. This effort is hampered by the fact that some examples were never gilded or have lost their gilding and that there are variations in size between examples.[9]While more work has yet to be done on these intriguing and beautiful objects, the original design remains one of the most beautiful and prolific of Renaissance Italy.

Drop-front caskets of this kind probably first appeared in Germany around the middle of the 16th century and soon became popular in Italy, the Iberian peninsula and elsewhere. Having various names depending on origin, time period, and intended use, they were frequently used by merchants as a writing box during travel and trade, coffer storing important documents and valuables, jewel casket, table box, etc…

1. Charles Avery, “Fontainebleau, Milan, or Rome?: A Mannerist Bronze Lockplate and Hasp”, Studies in the History of Art, vol. 2, Symposium Papers IX: Italian Plaquettes (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1989), pp. 291-305

2. Charles Avery, “Fontainebleau, Milan, or Rome? A Mannerist Bronze Lockplate and Hasp” Studies in Italian Sculpture (London: 2001), pp. 339-86 (this is an extended version of his 1989 article of the same title); and Lukas Madersbacher, “Armorial Lockplates: A Story of Success in Renaissance Rome”, The Rijksmuseum Bulletin, vol. 69, no. 4 (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2021), pp. 303-303-321.

3. Madersbacher, pp. 303-304.

4. Ibid., p. 305.

5. For an example with the same coat-of-arms see, Charles L. Venable, Decorative Arts Highlights from the Wendy and Emery Reves Collection (Dallas: Dallas Museum of Art, 1995), p. 15.

6. Madersbacher, pp. 317-318.

7. For a very brief encapsulation of the artists life and work, see: the Wikipedia entry for “Giacomo del Duca”.

8. For images of such surviving chests, see Madersbacher, p. 305.

9. Based on Avery’s inventory the majority of these lockplates are about 18 cm. square, with larger and smaller variants on either side of that measurement. For one of the smallest examples, which some believe to be a 19th-century example after the original, see Christie’s Auction Catalogue (London, 31 Nov. 2010), lot 423.

Acquired from highly reputable auction house Heritage Auctions, Dallas, Texas. Catalog: 2022 June Fine Furniture & Decorative Arts Signature Auction #8085.

Dimensions: (approx)

8.25″ High, 7.5″ Wide, 6″ Deep

- Dimensions

- 7.5ʺW × 6ʺD × 8.25ʺH

- Styles

- Period

- 19th Century

- Item Type

- Vintage, Antique or Pre-owned

- Materials

- Bronze

- Velvet

- Condition

- Good Condition, Original Condition Unaltered, Some Imperfections

- Color

- Brown

- Tear Sheet

- Condition Notes

Overall a superb example. Attractive appearance; structurally sound; beautifully aged patina over the whole; wear consistent with age, losses to …

Overall a superb example. Attractive appearance; structurally sound; beautifully aged patina over the whole; wear consistent with age, losses to veneer; scattered professional restoration, especially to interior drawers.

Be the first to review “Antique Italian Jewelry Box Casket – Attributed To Jacopo And Lodovico Del Duca” Cancel reply

Related products

Boxes

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.